[Hi there! Welcome to the second part of a longform series telling the story of our journey enhancing environmental justice (EJ) across Ladakh—one the world’s most stunningly beautiful, remote and militarized regions (read the first part here).

Our aim with these stories is to share a completely unfiltered account of our EJ work deep within the third pole, a region for which even the 1.5°C scenario is too hot. Since 2021, we have built that justice work from the ground up at Dharamshala—home to the Tibetan Government in Exile and His Holiness, the XIV Dalai Lama. We have written about it all and more in our archives, so happy reading and enjoy the photographs!

One more thing before we delve into Baltistan—if you’re someone who has an Indian bank account, please consider giving to the Center. We’re on ground, with no foreign funding, doing work that honestly impossible to execute from cities—laying foundations for EJ in the third pole. Your support counts for something as real as the photographs you’re going to see below! If you have any questions or thoughts, do reach out to us at himalayanadvocacy@gmail.com.]

Our task going in was simple, to reach as far into Ladakh as the Indian state would allow us as citizens and make our environmental justice work accessible from there.

We reached pretty far as it turns out—to places literally bordering Pakistan and China occupied Ladakh—we’re talking meters away.

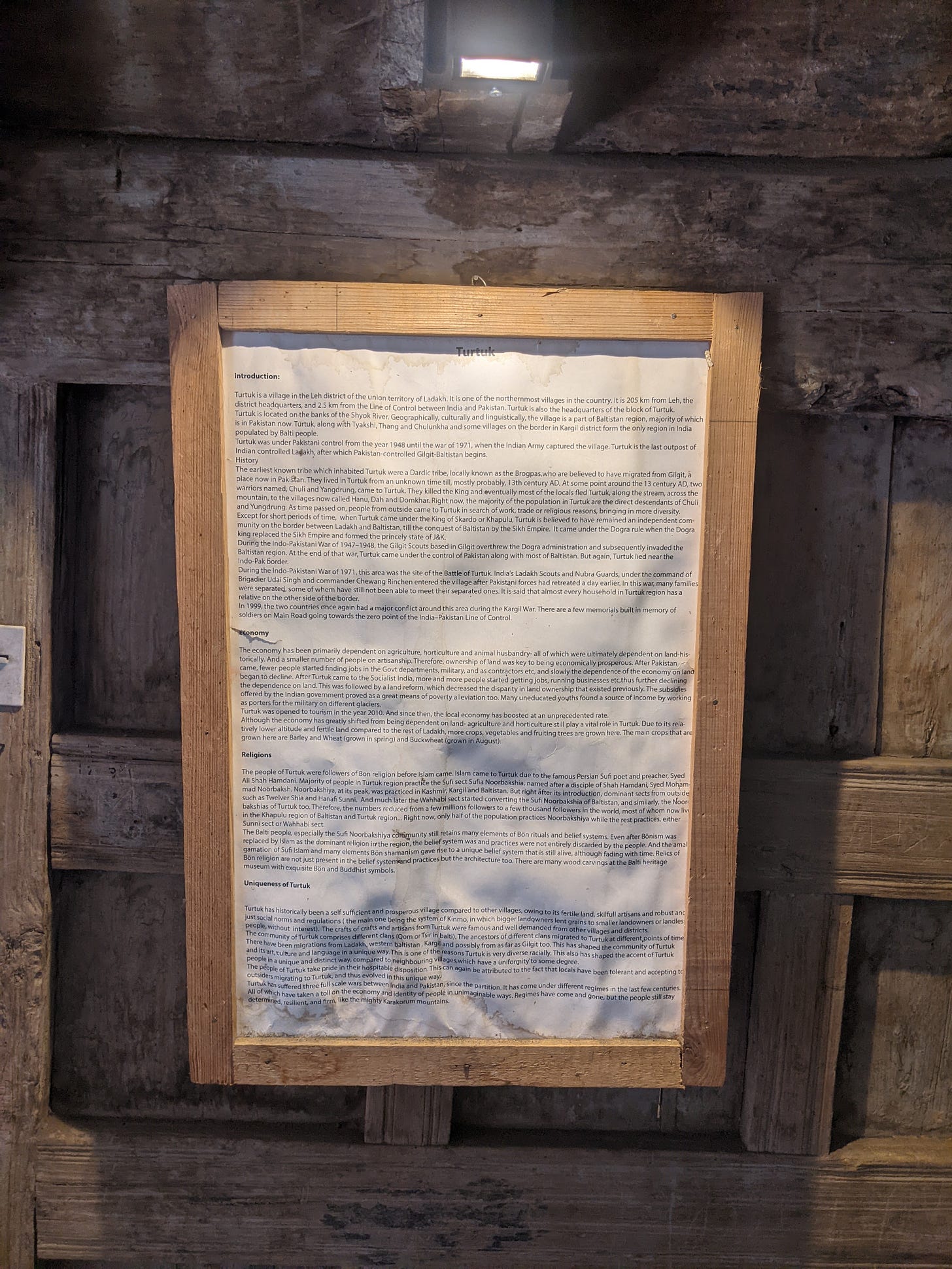

Today, we will take you through those portions of Baltistan that India fought and regained in the 1971 Indo-Pak war—the battle of Turtuk to be specific.

Wait but what is Baltistan? Here’s a (rough) map:

Before 1971, the Line of Control used to cross the bridge just ahead of a town called Bogdang. Beyond that bridge, the entire territory was under Pakistan’s control. The line now stands between Thang (on our side) and Fraono (on Pakistan’s side), which is about 30 kilometers deeper into the valley.

Here’s a map to explain:

Zoomed out a bit:

This is the Bogdang bridge:

Wondering how the Shyok river looks like from this region? Dangerous, in one word:

This video, BTW, is from the last bridge before the Shyok enters Pakistan occupied territories.

Anyways, as we mentioned, the terrain after the bogdang bridge changes—it becomes a lush valley—a glaring exception when it comes to Ladakh. This is how Baltistan looks like:

We had to stick our stickers across the valley, and fortunately, our host was super stoked about it too—he put up three at the homestay for each room and even the local Anganwadi, or Government run Cresh and all round women centric welfare space (this sounded too good to be true when it happened, honestly):

We also had a good meeting with two primary school teachers from Turtuk, along with Abdul, our host.

We introduced some of what we do—the entire logic of putting crucial environmental information into the hands of local communities—in a form they can easily navigate and use—in times of injustice.

Our own experience in a small Himalayan town has taught us that communities often use such information in pithily novel ways—like the simple visual of showing a court order to an official, or even as an annexure to a petition.

[In line with our track record, we’re going to casually drop a mega annexure here—where a National Highways Authority of India appointed expert committee actually agreed that four laning highways in the mountains might not be a good idea.]

Back to Turtuk. Our focus though, was much more on listening what they had to say—about how organized local self government is in the village, with a Trust incorporated specifically to deal with social and educational issues, for example. The issue of solid waste mismanagement and stone mining in the valley also came up, besides their ambition to continue teaching and serving the community.

We savored some mulberries, wrote a message for the future generations of Turtuk on our paperback and handed it over to them along with a few stickers, with a realization:

Teachers are the weavers of intergenerational equity.

That’s right, isn’t it—not presidents, lawyers, engineers, doctors or scientists, but teachers. Think about just how formative our years in primary school have been for us and our parents!

Handing over the paperback to them felt like we’d done something worthwhile. It also brought to light just how much more work is left to make legal language simpler—after all, literally no one on the planet except lawyers understands what “locus standi” or “stare decisis” means.

Anyways, the architecture of Baltistan is as beautiful as its mountainscape:

We’re saving the best of the best for the last—pictures from Thang, a village located AT the line of control between India and Pakistan. Yes, EJ stickers reached Thang as well—just like magic!

Well, this was a long one but hopefully the kind of newsletter you would enjoy—covering a lot of issues, and more photographs, from regions as remote and real as they can get. Oh wait—we’re going even more remote in the next newsletters, so stay tuned. We’ll leave you with a photograph from the world’s highest battlefield, Siachen glacier:

Happy monsoons (stay safe)!

Himalayan Advocacy Center

Postscript:

As you may know, we are a small non profit in the environment + law space located in the Indian Himalayas. We are completely bootstrapped! This means no foreign funding and no fancy headquarters - just a small community - of which you all are an integral part - in the long run we hope!

What’s more - we, at the Center, are determined to localise efforts for the planet, without compromising on the best that the law has to offer. If you have the means, and want to support a committed local undertaking, please do consider contributing to our corpus. We hope to pleasantly surprise you with detailed information on where you money has been spent.