I'm an Indian Environmental Lawyer. Here's what I Witnessed in Kashmir.

The Dhauladhar Longread #2

[On 22nd April, 2025, a terror attack took place in the Baisaran meadows in the upper reaches of Pahalgam, Kashmir, resulting in the massacre of at least 26 civilians, as of the 23rd April, 2025.

This attack is deeply connected to Kashmir, and thereby this newsletter—where we discuss a field visit to the valley, that took place barely a month before this incident.

In light of recent events, we are publishing this longread virtually as it stood before the massacre—revisiting existing portions with care and intention, while striving to maintain an authentic account of our work in the valley, in line with the Indian Constitution. Part two of this longread will follow soon.]

Prologue

By now, the tires had lost all traction, and the snow had started making its way up my knees. I stood there—taking in the views of the March snowscape, melting icicles, and thousands of conifers, many of them probably more than a century old.

At a distance, I heard the ravens, and echoes of someone slowly chopping wood, probably for fire or to patch a broken attic. The Kalaroos valley far below resonated with the Zuhr Azaan—second of the five daily Islamic prayers.

I decided to trek to Zamindar Gali, two kilometers uphill, as the local SUV taxis with their snow chains passed by. Taking advantage of the predicament, I continued sharing our environmental justice stickers along the way—with discerning locals, on roadside crash barriers, and outside Karyana stores.

As soon as I reached, a visibly on-edge military man stopped me from using the camera, and asked me to show him the photos I’d been taking. He proceeded to delete some—a standard practise, he reminded me.

At this point, I was standing about 30 kilometers from the Line of Control between India and Pakistan. On a clearer afternoon, one might have observed the mighty Nanga Parbat from the Gali.

I was told to head back.

It was probably too risky—for reasons best known to the military—to let an outsider walk amidst 6 feet of snow, towards a border no less—with our “friendly” neighbor.

The military was on edge for good reason.

“Some soldiers were brutally killed in this area a few years ago. The military has become extremely strict since then”, said a local boy who had hitched a ride with me on the way back. “Cross border shelling is common in some of the frontier regions where we live. They don’t target settlements, though. Both sides strike the forest regions around military camps. It is a performance of sorts”, he added.

“At times, it is easier to talk to outsiders, who come in with a blank slate”, he said when I asked him about the surveillance situation.

“Why have you come here? You should have gone to Gulmarg or Pahalgam. There’s nothing here. This is a “dodgy” place, and the people aren’t nice”, said another military man at a checkpost on our way back towards Kupwara, as he handed back photocopies of the ePass and ID that I had submitted with his colleague earlier.

The boy stood absolutely silent, looking the other way—trying not to be noticed.

“Most of my family lives in Azad Kashmir. We can’t even talk to them now. If the military finds out, we’re rounded up, harassed and beaten”, he later lamented.

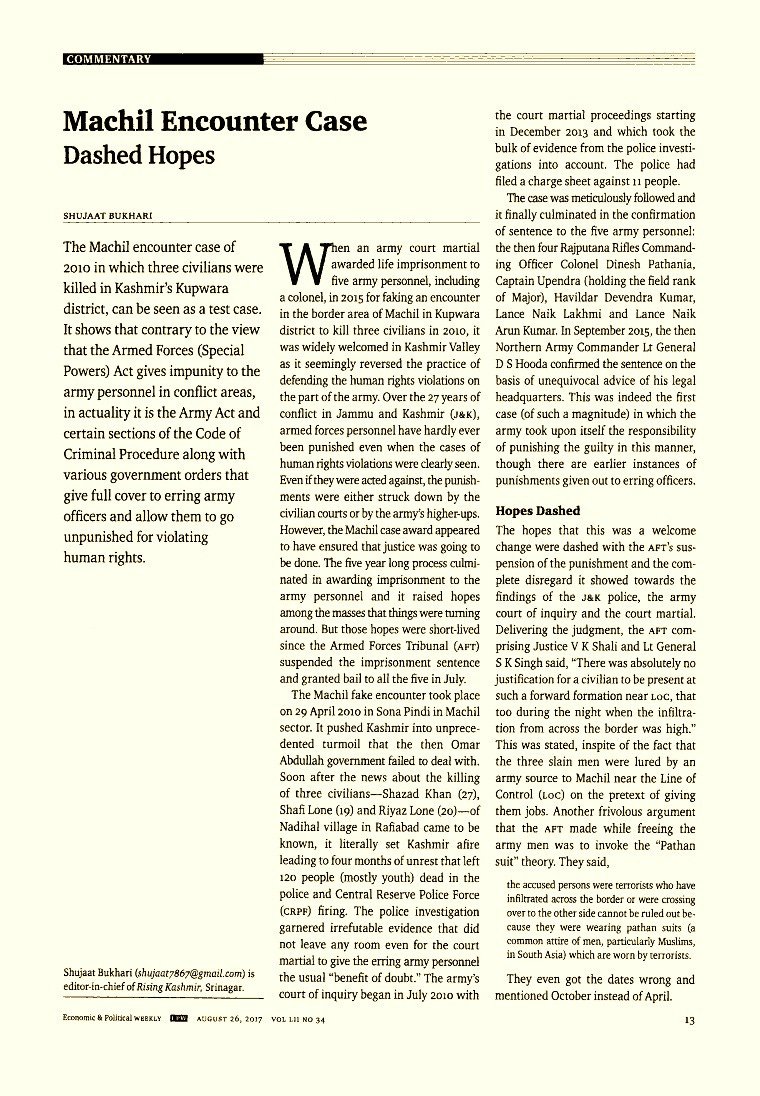

Machil has been at the literal frontline of the Kashmir conflict. This is where the 2010 fake encounter took place, leading to the subsequent unrest across the valley, that left 120 dead.

So why did I go to Kashmir, and why pursue environmental justice work within the most militarized place on Earth?

Find out in this longread! Let’s start at the beginning, with introductions.

Hi friends, hope you’ve been well!

I’m Utkarsh, a member at Himalayan Advocacy Center, and devout mountain person. I’m writing to you from Dharamshala, where Himalayan Advocacy Center is based, on a beautiful spring day in April, 2025.

The Preface

Narration and limitations

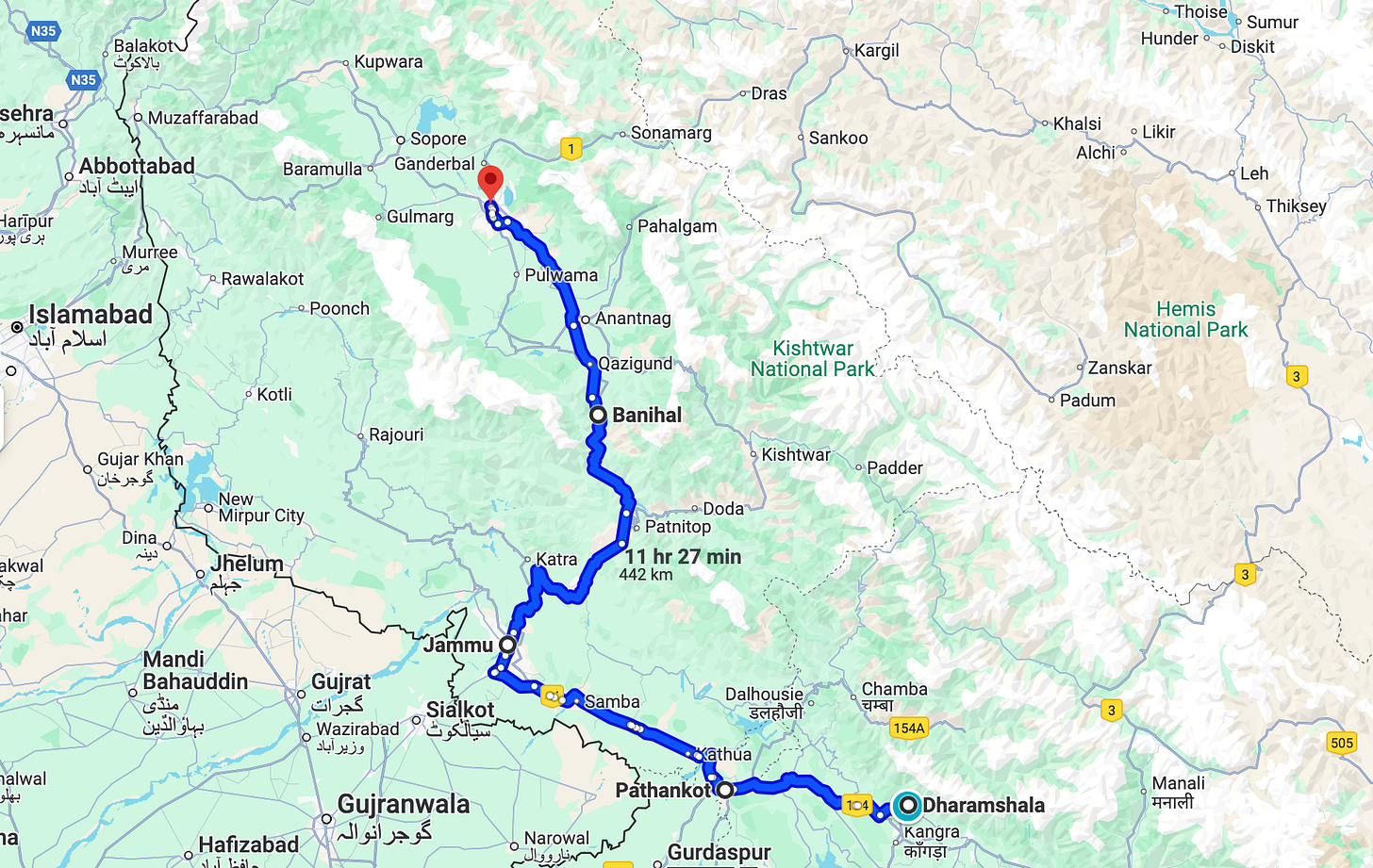

This longread is about my experience travelling ~600 kilometers within Kashmir, in particular its northern regions—from the 14th to the 21st of March, 2025, during the holy month of Ramzan.

This time around, I’m parting ways from the usual, third person style that The Dhauladhar has followed in the past 31 issues.

I get the sense that writing in an individual capacity opens up space for more nuance—something that I have learnt—from poetry, hiphop, photography, interviews, syllabi, reportage, documentaries, recent academic literature from after the abrogation of Article 370, and podcasts—that us “outsiders” might need more of, when it comes to Kashmir.

Space for more presence too. Writing in first person allows me to immerse within context in a way that organizational reporting wouldn’t, for a non-journalist anyway.

I’m also an Indian—and an Advocate—working for a nonprofit in the EJ space, registered under Indian law. That fact places certain constraints on me, which I hope we can explore together in this piece—by leveraging our own unique sensibility, context and heritage.

I want to bring to fore my identity as an Indian writing about Kashmir, as a means to an end: presenting as close a picture of the ground reality in the valley—as my own limitations and circumstances would allow.

At the same time, being an Indian citizen grants me certain unique privileges. As a citizen, I’m in a position remind the State, as appropriate, of its bounden commitment to the Indian Constitution, its basic structure, and the system of international law that the State has explicitly agreed to be bound by.

Why Kashmir, and for what?

Why go to the valley in the first place?

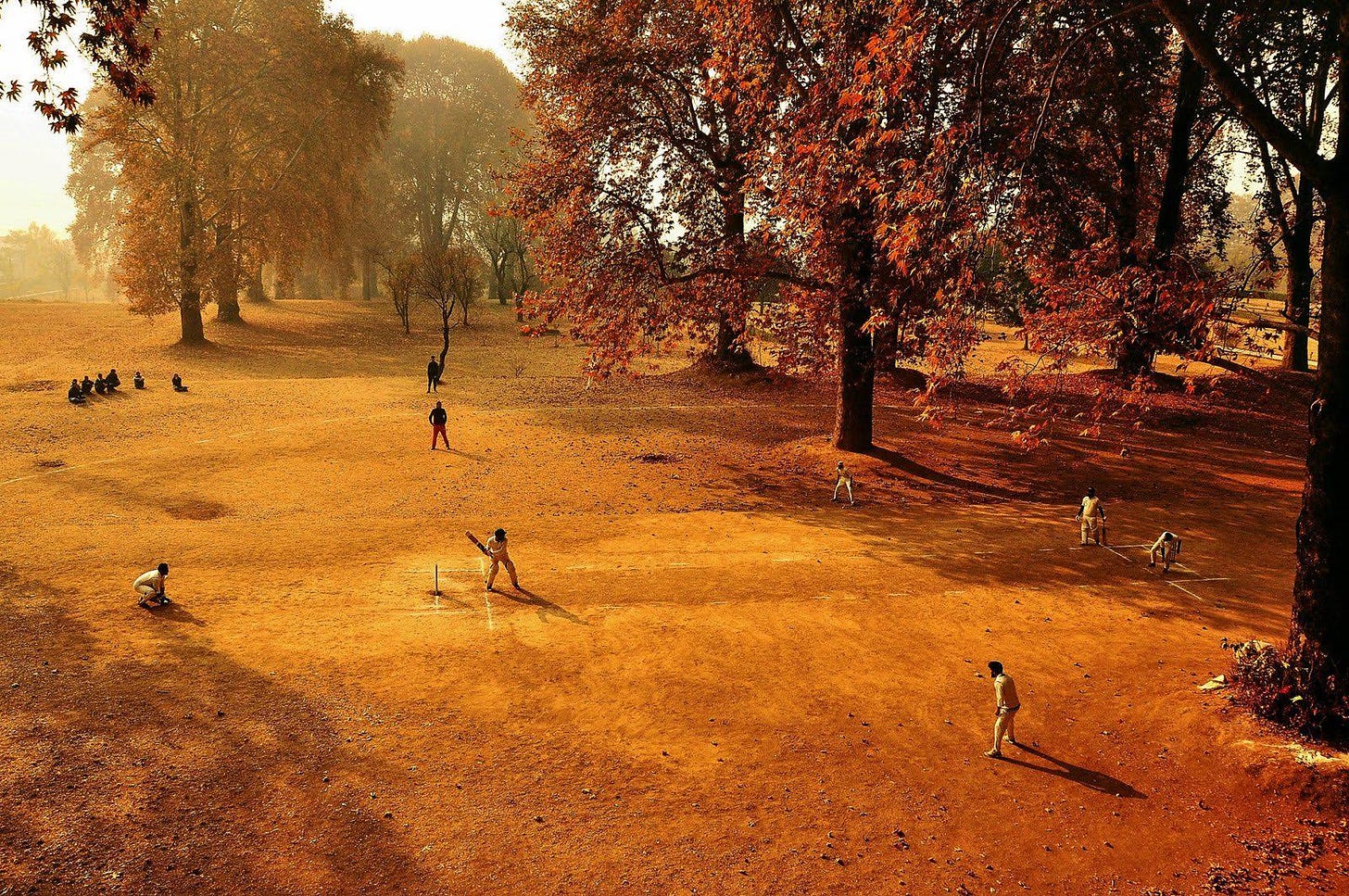

Well firstly, there might be no other place on the planet that is as breathtakingly beautiful as Kashmir.

I went with the aim of sharing our own EJ work at Himalayan Advocacy Center, with locals—Kashmiris, Pahadis, Pakhtuns, Pandits, Sikhs and whoever else I could find.

This work includes a burgeoning syllabus of judicial precedent and primary sources of information concerning the state of the third pole environment—that we at the Center have gathered from the Indian state, and organized over the past few years.

The underlying purpose has been to create a substantive dossier, that can be leveraged to hold the Indian state accountable to its own word on the environmental rule of law—including within Kashmir.

Leveraged how? As an irrefutable exhibit, piece of evidence, justification, proof or generally, a basis—building on existing community claim to EJ within the valley—created within and from the third pole region.

Here’s an example of what this could look like as part of advocacy efforts demanding that India adhere to its international commitments as they relate to the “interface between human rights and the environment”, among others:

After having visited Kashmir, there is no doubt in my mind that it is a warzone—where India and Pakistan (and China) continue to deploy their most advanced military technology. This is its ultimate paradox: a warzone that is also one of the most beautiful places on the planet.

A natural fallout of this paradox is that the rule of law in Kashmir remains in dire straits, let alone the environmental rule of law, and Indian environmental law. This was my second, larger reason for visiting—learning from, observing, and documenting environmental issues in the valley.

Another way to look at this is that Kashmir is one of the few places on the planet where one can witness the limits of “law” and “justice”—philosophically, historically and viscerally. An place to actually learn where any system of law, including environmental law, is falling terribly short in today’s world.

The fallout is so total, that it is impossible to segregate one issue from another, and even get a sense of it all at first. It should be obvious then, that we need to pay close attention to how people in warzones such as Kashmir are grappling with these issues—for the understanding we will end up gaining, will be far more valuable than what any University has to offer.

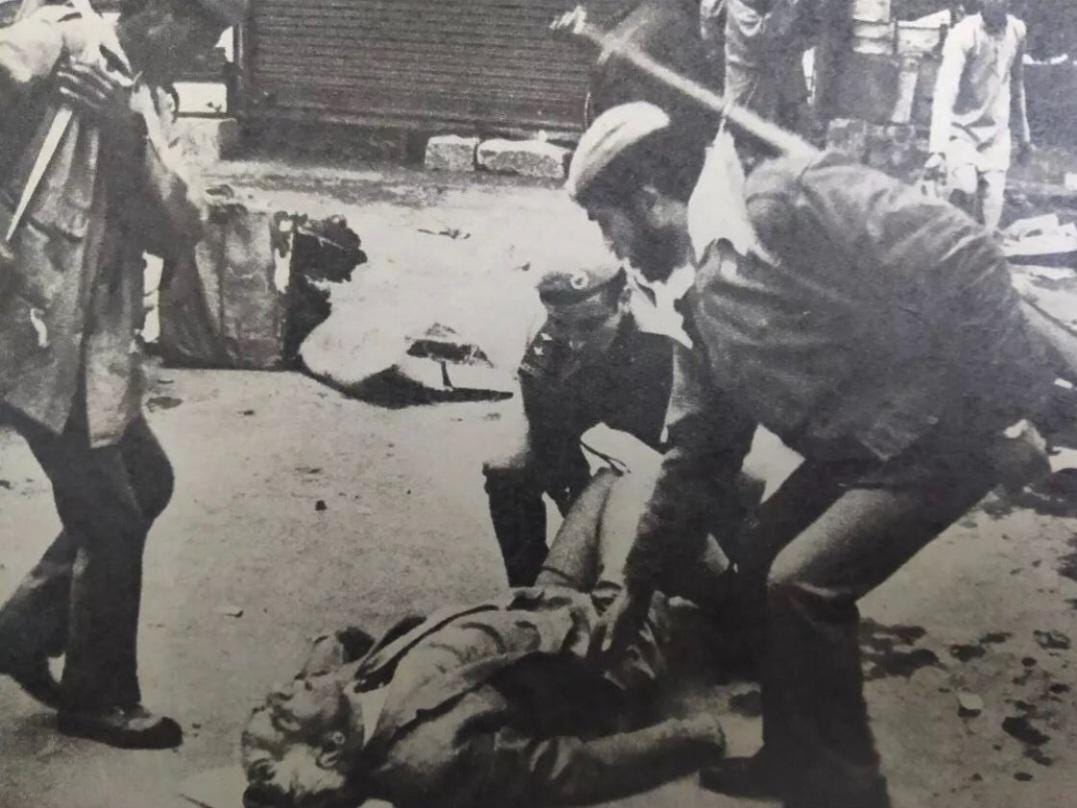

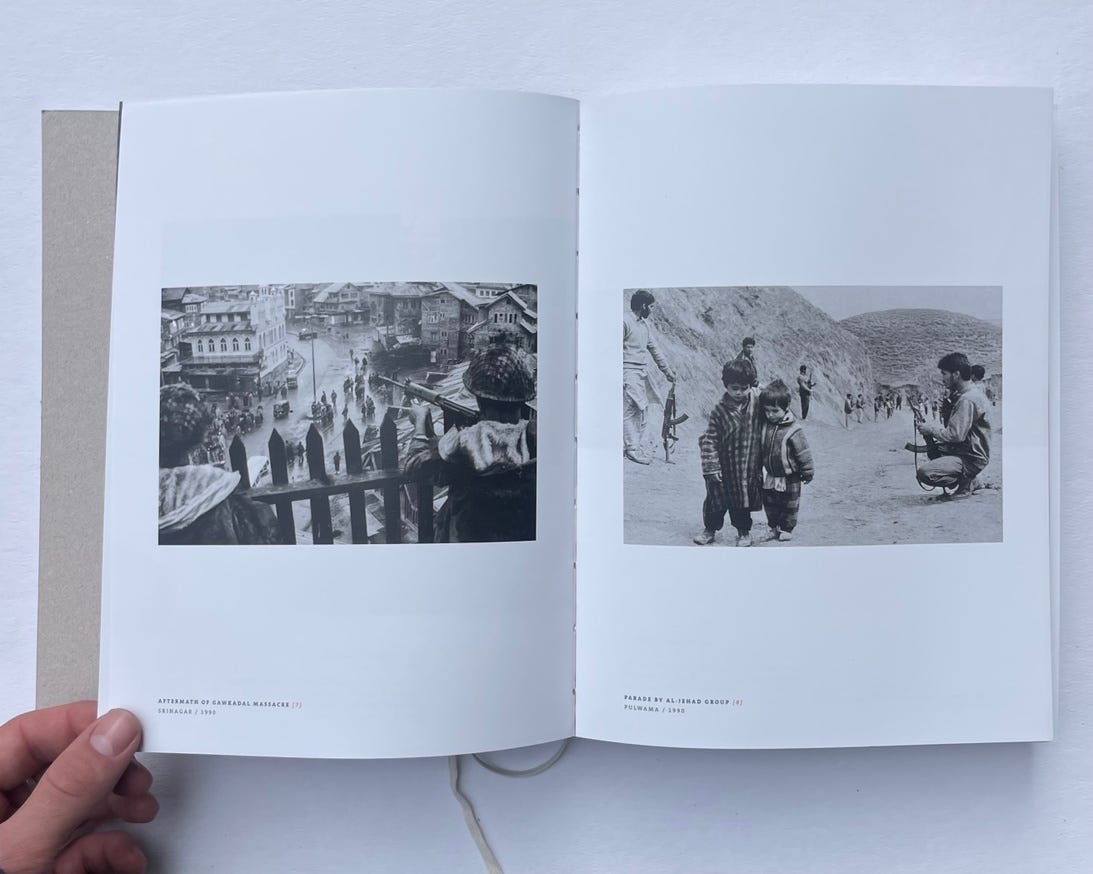

Photographs that depict the forms that these “limits” on law and justice continue to take:

Sharing relevant legal resources, that enhance existing claims to EJ—with key stakeholders within such a region was therefore an intuitive next step to take in our organizational journey.

In this process, my aim was also to double down on our stated commitment at the Center, to stay true to the ground reality by locating ourselves within the region and amidst the people we want to work for.

[Last year, we executed similar work in neighboring Ladakh as well, reaching even closer to the Indian frontier with Gilgit Baltistan, East Turkestan and Tibet. Check that out here.]

The Logistics

The purpose of this section is to be transparent, and put on record the logistics—including budget, equipment used, and routes followed.

I haven’t seen too many Indian nonprofits be transparent with their field visits. This must change.

I believe that transparency isn’t simply a mandate to be fulfilled at the time of annual filings, or in air conditioned boardrooms with philanthropists. In being transparent, we’re simply making it easier for others to take our work forward—should they decide to venture out themselves—like those that before have done.

I also see transparency as a form of gratitude to our supporters, who made the decision to fund this visit in various forms, and to whom the Center remains accountable.

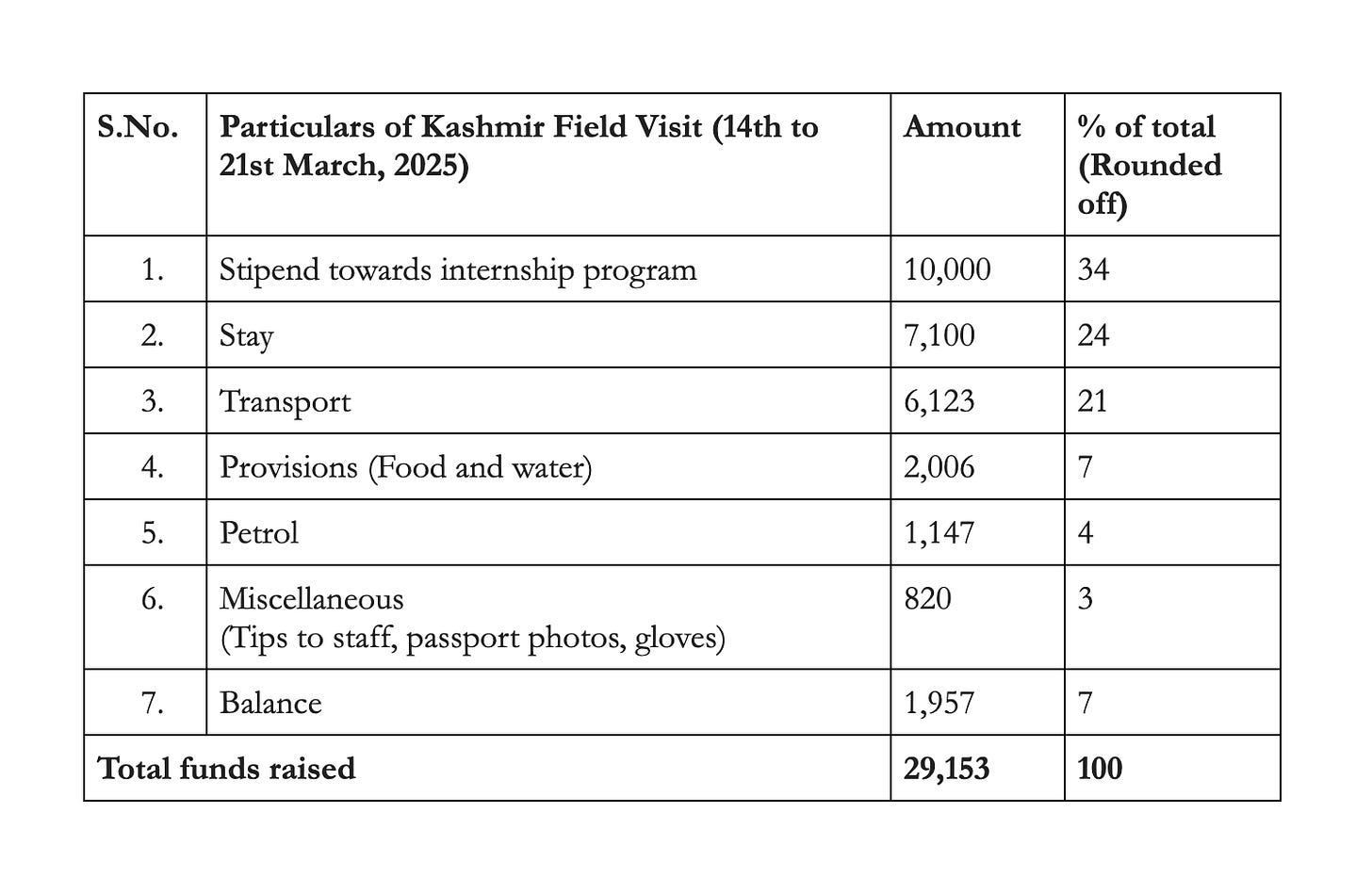

Budget

The initial target set for the trip was ₹15,000 (~$172 as per the figure of ~₹87 to the dollar in the second week of March), but I ended up raising almost double that, thanks to the generosity of the community.

With no fundraising experience, it took me 51 days to raise ₹29,153 (~$335), to manage about 7 days worth of field time, and pay staff who assisted with the planning phase.

Here’s the Canva flyer from the LinkedIn post wherein I first introduced the idea of such a field visit to the community—as part of fundraising on the 22nd January, 2025:

Ultimately, I realized that only a very small percentage of funds raised (>5%) actually came in through social media. The remaining came through direct outreach with contacts, largely from the legal fraternity and locals.

Here’s the breakdown of the budget:

As you can see, the largest share of funds went towards paying colleagues.

The amount I ended up spending on food was comparatively much lesser, considering it was Ramzan time—and somewhere, that had an impact on how much I ate, even as a non-muslim. Many times, locals invited me in to have a meal with them, offering kulchas, bakerkhanis and cups of nun chai. Without exception, everyone I met on the road offered to host me for a meal, or even to stay at their home. I am grateful to Kashmiris for subsidising the visit in a big way—with their time, experiences and resources—their khidmat.

As regards accommodation, everyone has different standards and priorities, but I found safe and clean places to stay in the 1,000 to 1,500 per night range (with the exception of Jammu, where I didn’t get enough time to find a decent place). Prices also change depending on when you go, but finding a good bargain isn’t that difficult. The longer you stay, the better the price.

A boy from Handwara who I had dropped in downtown Srinagar on my way back from Sopore generously offered to show me the entire Bangus valley, and a stay at his village—a gesture that I was frankly not used to, coming from mainland, largely urbanized India. This is another way in which Kashmiris offered to quite literally fund my trip through their land, before even getting to know what I went there for.

Getting receipts wasn’t always easy.

Many people didn’t have official bill books. I went prepared for this, having asked my Chartered Accountant about the use of kacha, or handwritten bills. My standard response to curious folk who asked me what I needed the bill for was “company ki taraf se aya hu, upar dikhana hota hai” (I have come on an official trip, need to show this to the higher ups).

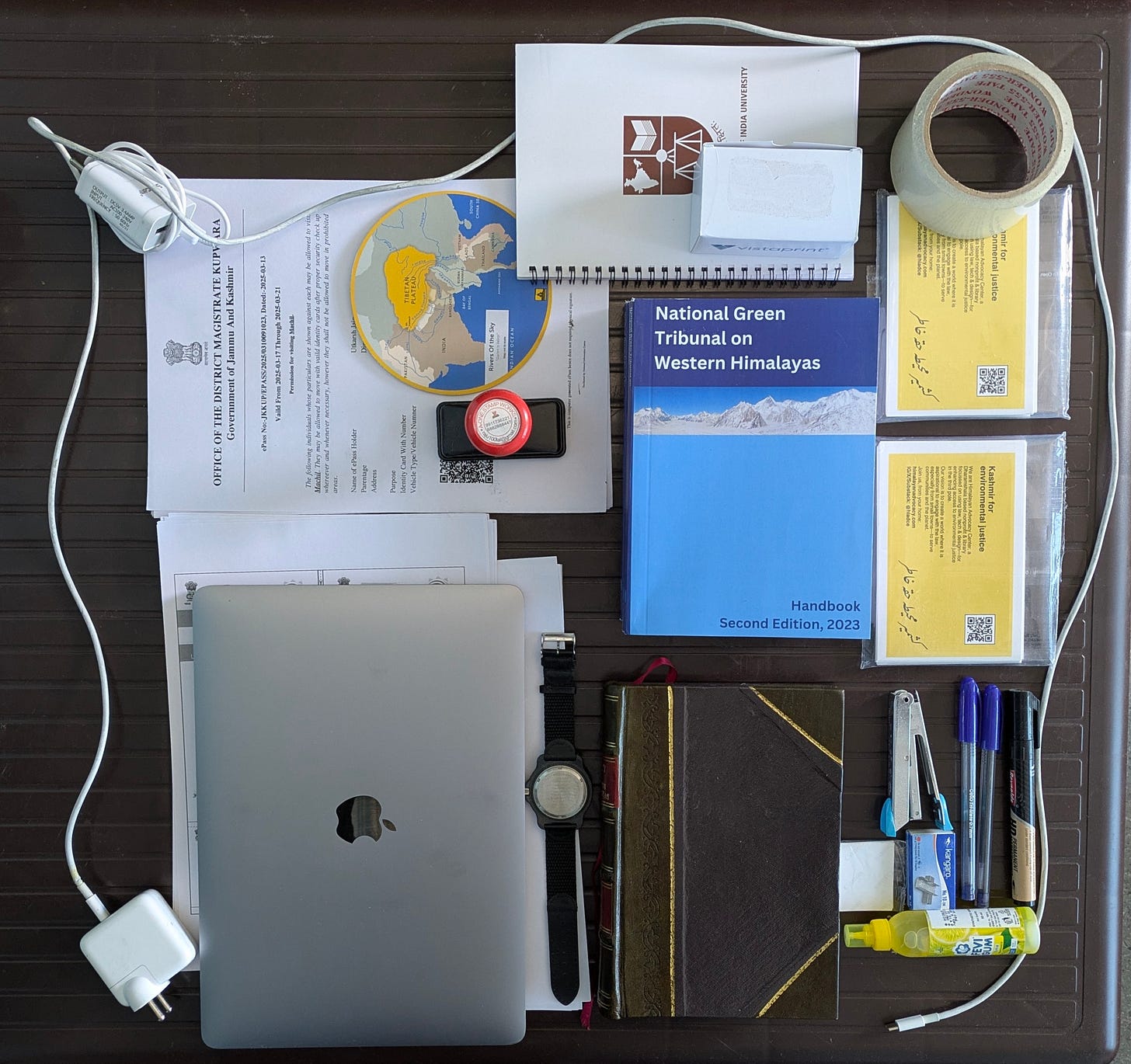

Equipment

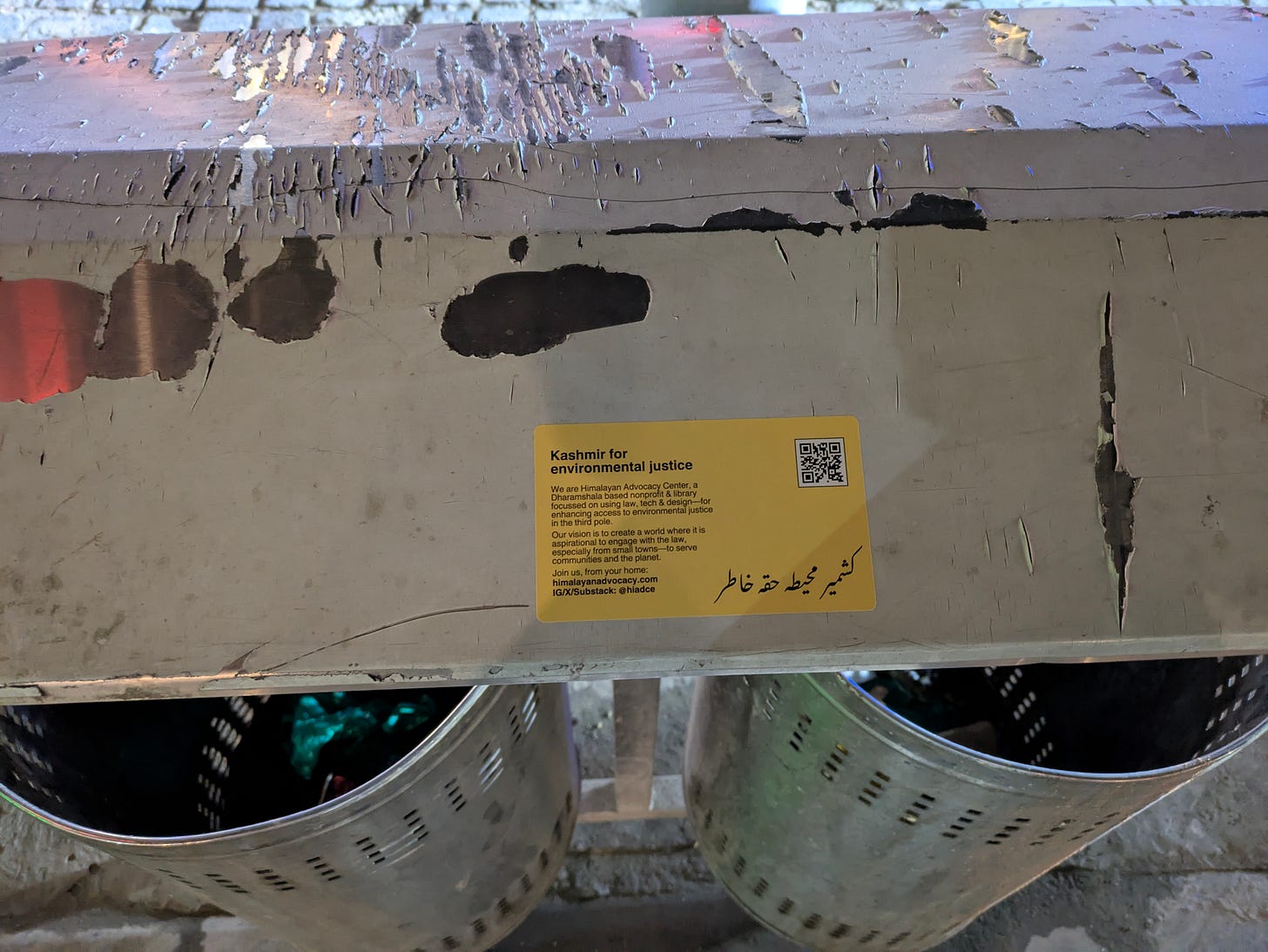

While there is no special list you need to make for Kashmir, except for permits to visit restricted border zones—the specific work profile meant that I did carry some of our printed EJ work and necessary stationary.

These EJ stickers formed a core pillar of the visit.

They made it possible for anyone to access thousands of pages of environmental information we have been gathering—with a simple scan, using their smartphone.

Unfortunately, the Kashmiri portion, which was meant to translate “Kashmir for Environmental Justice” ended up completely wrong, but at least we had an English version to accompany.

Carrying two bags on a scooty with a helmet on did put the military on high alert at times, especially when I passed anti sabotage checks, where dozens of fully decked out soldiers, army dogs and anti-mine vehicles check entire stretches of road, for bombs or other such explosives.

I was stopped or told to slow down while passing many such movements. At other times, the soldiers loudly whistled at their colleagues to let them know someone was coming in from behind.

It was a very unnerving experience.

I would have definitely turned back without attempting the Gali, had it not been for two old men—getting ready for their prayer—who reassured me that it was safe to ride through to the top.

Routes

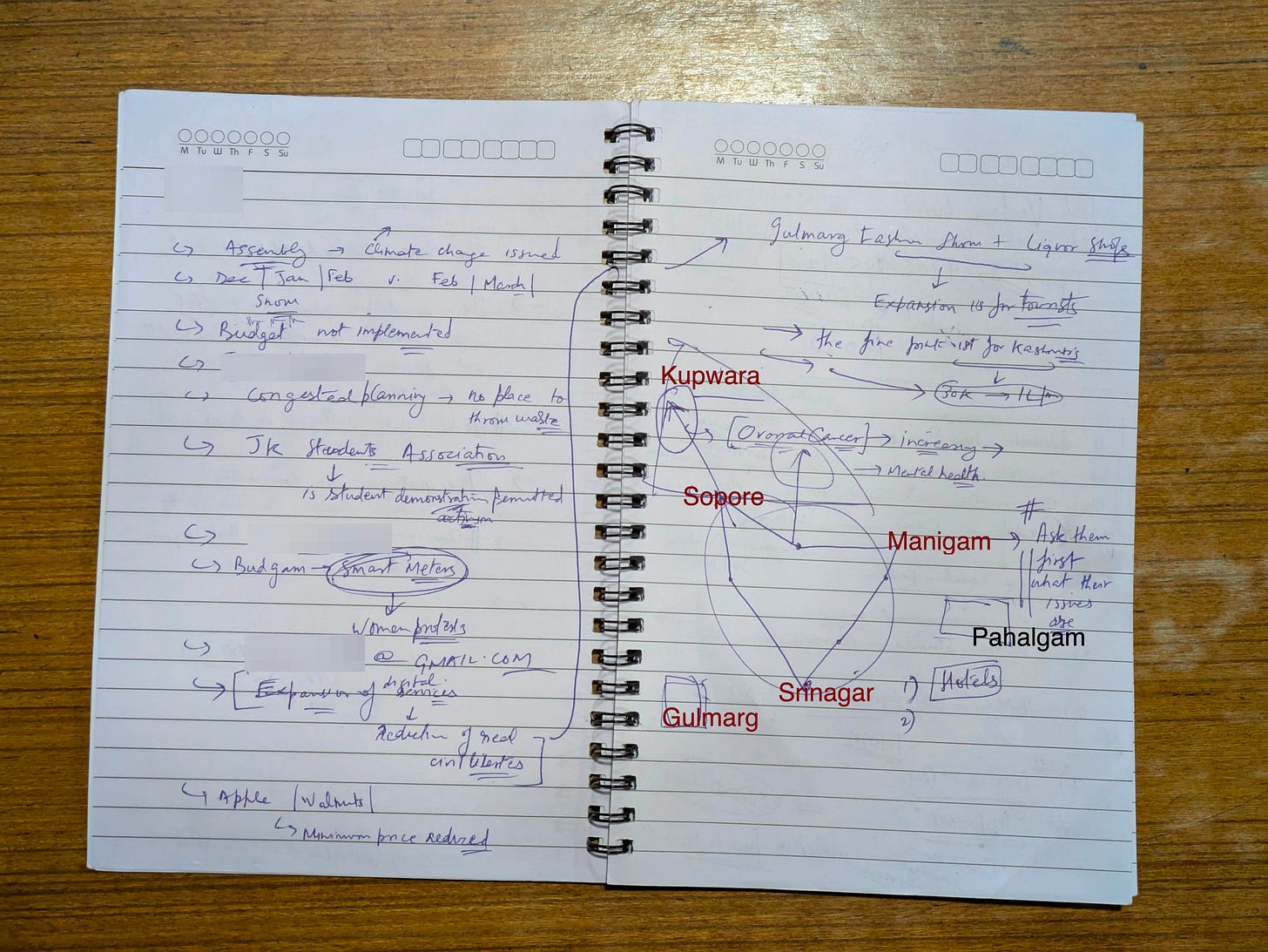

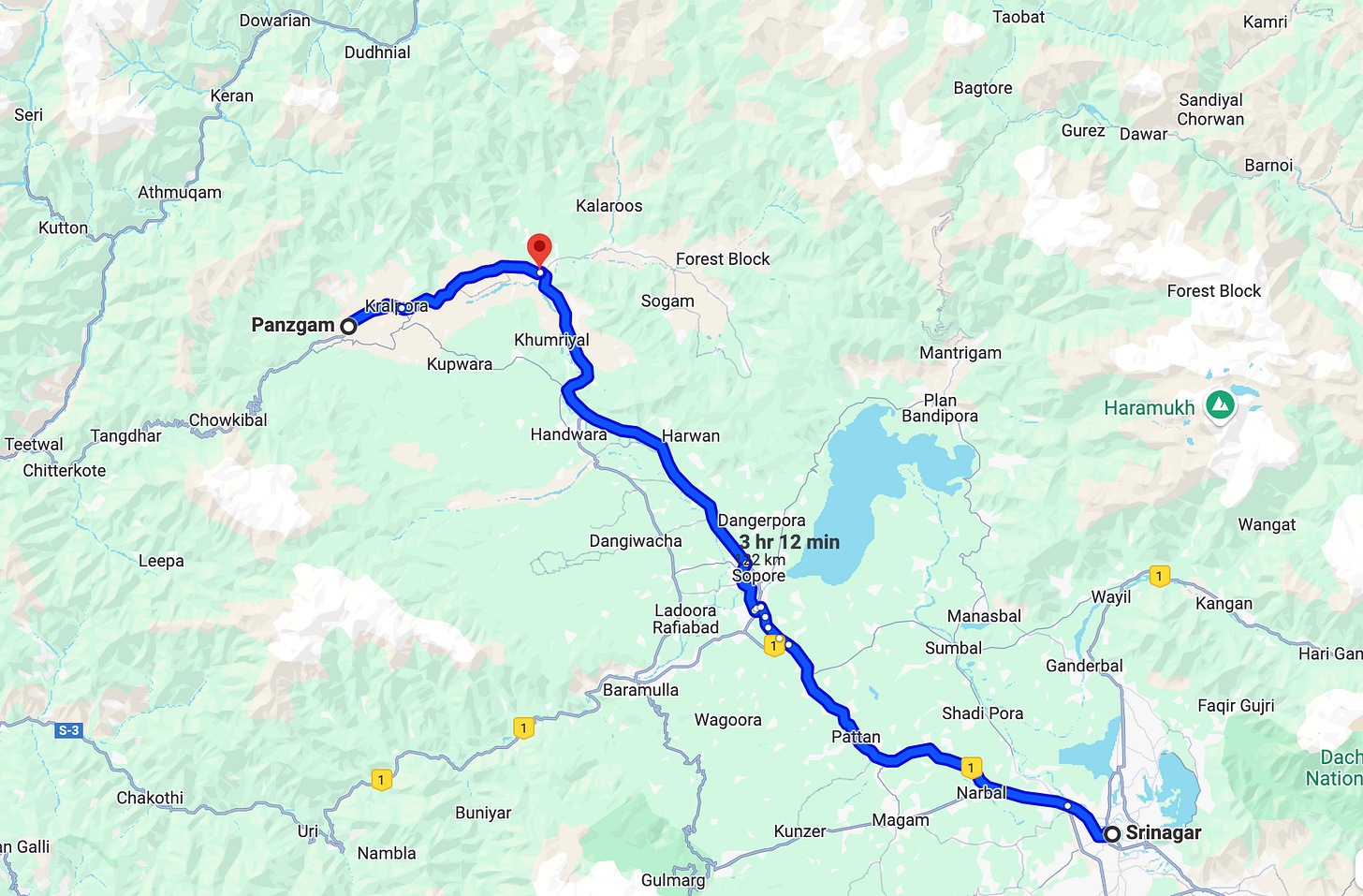

The purpose of this section is to lay out the locations I covered during the visit, and how I navigated my way around the valley—for anyone interested in venturing into North Kashmir for ethnographic, legal, or environmental work.

There was only so much I could cover in less than a week, but on the advice of a local well-versed in the environmental issues facing the valley, I decided to prioritize Kupwara over the more mainstream destinations of Gulmarg and Pahalgam.

Reaching Srinagar

Himachal Pradesh Road Transport Corporation offers daily bus services connecting Dharamshala with Jammu. I got on the 9:40AM bus, and reached Jammu around 4:30PM, on the 14th.

The plan was initially to take another sharing taxi to Banihal, the gateway to Kashmir, and then get on the train to Srinagar next morning.

Unfortunately, there weren’t enough passengers for the Banihal ride, and after waiting for a couple of hours, I decided to directly head towards Srinagar, reaching at 3AM on the 15th—only to be greeted by freezing rain, and “unusually heavy snowfall in the higher reaches, for March” according to locals.

Fortunately though, the driver knew Sabir, who owned a couple of good hotels in town. He gave me a ride to a decent place in Rajbagh, with heated blankets and hot running water.

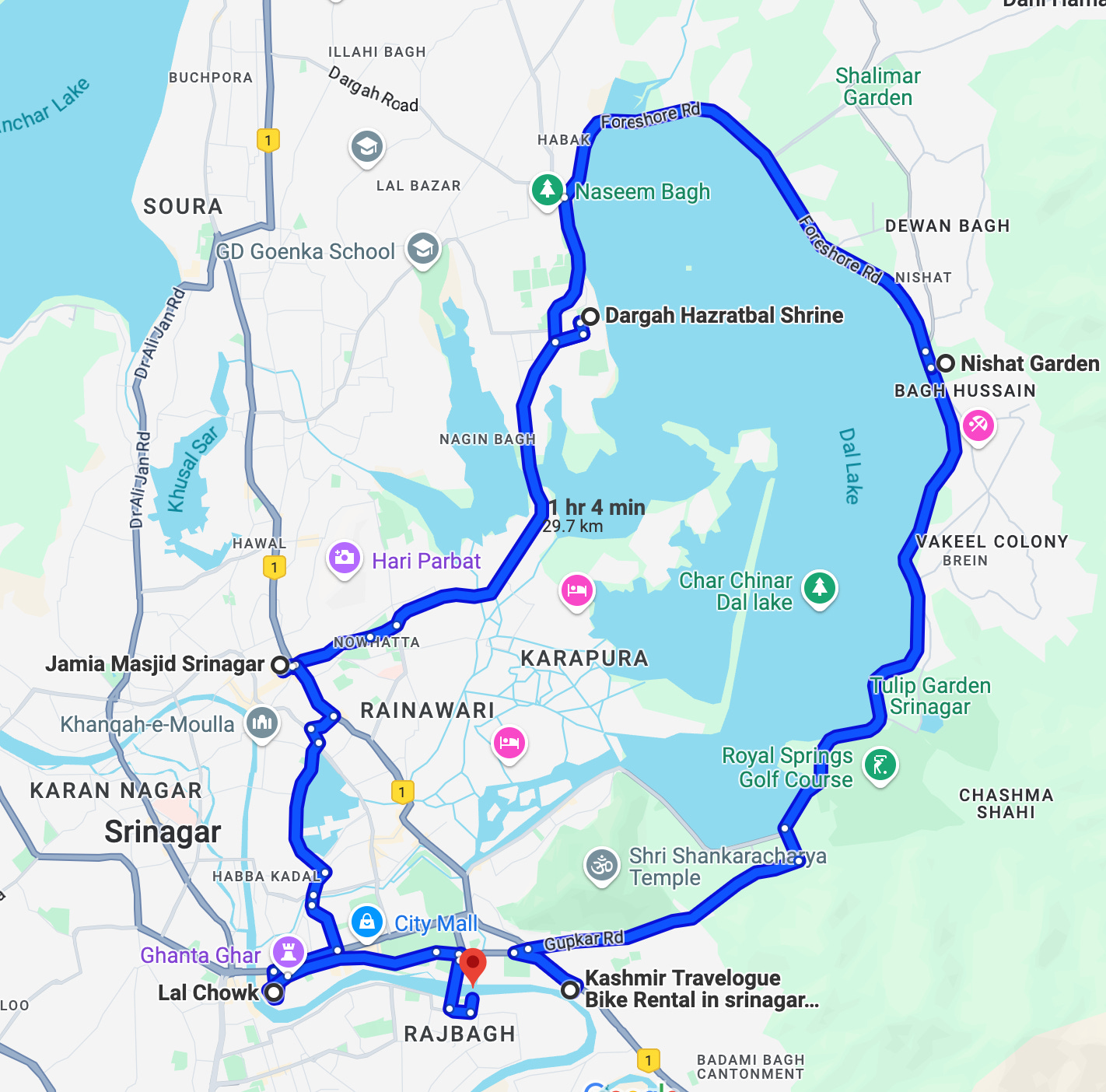

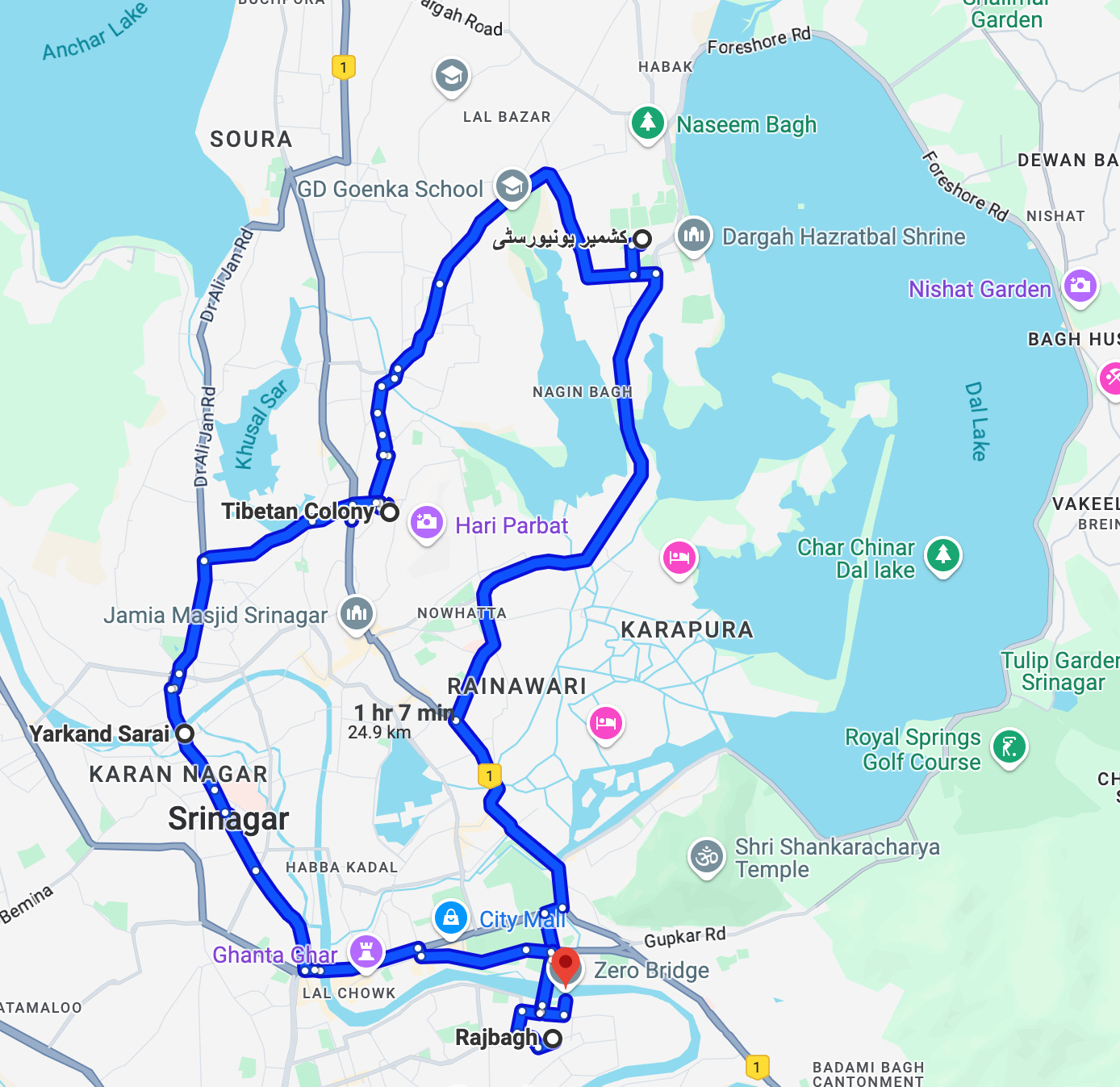

Within Srinagar

For a first visit, I managed to cover large portions of the city on bike as well as by walking, covering major neighborhoods—including Rajbagh, Sonwar, Downtown, Hari Parbat, Hazratbal and the Dal Boulevard Road area.

I highly recommend walking across downtown, to observe the dynamics of Kashmiri society amidst intensive military presence (more on this in the next sections).

I witnessed kids playing around in many parts of the old city, even as the evening gave way to night. At first, it made the place feel safe.

Walking upstream the Jhelum also gave me the opportunity to put up the stickers in close proximity to heritage structures that dot its path—including Temples, the original wooden bridges and Mazaars, and strike up conversations with locals.

Here’s one such (translated and contextualized) exchange with a retired Uyghur teacher from Yarkand Sarai:

“Salam Walekum! So, are you a researcher or student? Do you have some questions for me?”, asked an energetic old man, with distinctly mongoloid features, not too different from those at the Tibetan colony in Badamwari.

A kid who was playing there led me to him, when I asked about the history of the Yarkand Sarai. It was almost iftar time. “Walekum Salam! No no, I was just roaming around the place. Heard that this is a historical structure”, I responded.

I had always wanted to come here, ever since I visited the Central Asian Museum at Leh—to find real life remnants of the great cultural and trade links between Panjab, Kashmir and East Turkestan.

These linkages had been active well into the 20th century, ending soon after China’s invasion and occupation of East Turkestan in 1949, and the imposition of borders that separated Central and South Asia.

“So, how long have you been living here? Are you from here?”, I asked, encouraged after he mentioned that he was a retired teacher. “We live here now, this is where we are from”, he responded.

“I have something for you, since you are a teacher”, I remarked, giving him some of the stickers, and telling him about what I do.

“Oh wow, I will safely store it with me, many people some here and share their work with me. I’ll go through it. Add your postal address and other details here, so that we can be in touch!” I happily obliged.

“Do share it with your children and family members, and take care—I don’t want to hold you back at this time!”, I added in haste, knowing that his roza was about to end, with iftar time fast approaching.

The boy who stood at the gate offered to take me to the ruins of the long shut down place of worship. Assuming I was a Kashmiri Pandit, he asked me if I used to live here, and mentioned that people sometimes come looking for these temples.

Entering North Kashmir

I kept stopping along the way, to document the valley and share our work with the locals.

Putting up a sticker right on the display section of a nanwai ahead of Ganderbal was one of my biggest achievements. Where else can you expect hungry crowds to come at, after an entire day of fasting during Ramzan?

Border regions

At Trehgam, I noticed a local Sumo (SUV Taxi) stand in the middle of the market and decided to put up two stickers there. Three soldiers were standing guard, and asked me a couple of questions about my purpose of visit, place of stay and contact details. This was one day after the Zachaldara encounter, and probably a safety measure.

Towards Shimla

Kashmir / کئشر

Although my focus during the trip in terms of documentation was on videography—here are some frames I managed, that hopefully showcase the beauty of Kashmir:

On chancing upon a board mentioning SKUAST Faculty of Forestry on the way from Ganderbal to Sopore, I decided to explore in the spur of the moment—ending up deep within the Pakhtun part of Kashmir, in a village called Watlar.

I met a local Pakhtun elder (bewildered at my sight) constructing a stone house beside the school, and broke a few walnuts with him as his wife watched on—while discussing how long it would take to trek to Bandipore from Watlar. “I used to be able to do it in 3-4 hours, back when I was younger”, he said.

I handed him a few of our EJ stickers and my number, and requested that he share it with the school headmaster, who turned out to be his brother.

“Please have some dates … oh, sorry, I forgot its Ramzan” I later told the guard at the SKUAST gate while heading back, as I stashed the dry fruits in my pocket.

“No need to apologize, please have some”, he reassured me. “Apne ehtiram kiya, wohi kafi hai hamare lie” (It means a lot to me that you showed difference to my culture).

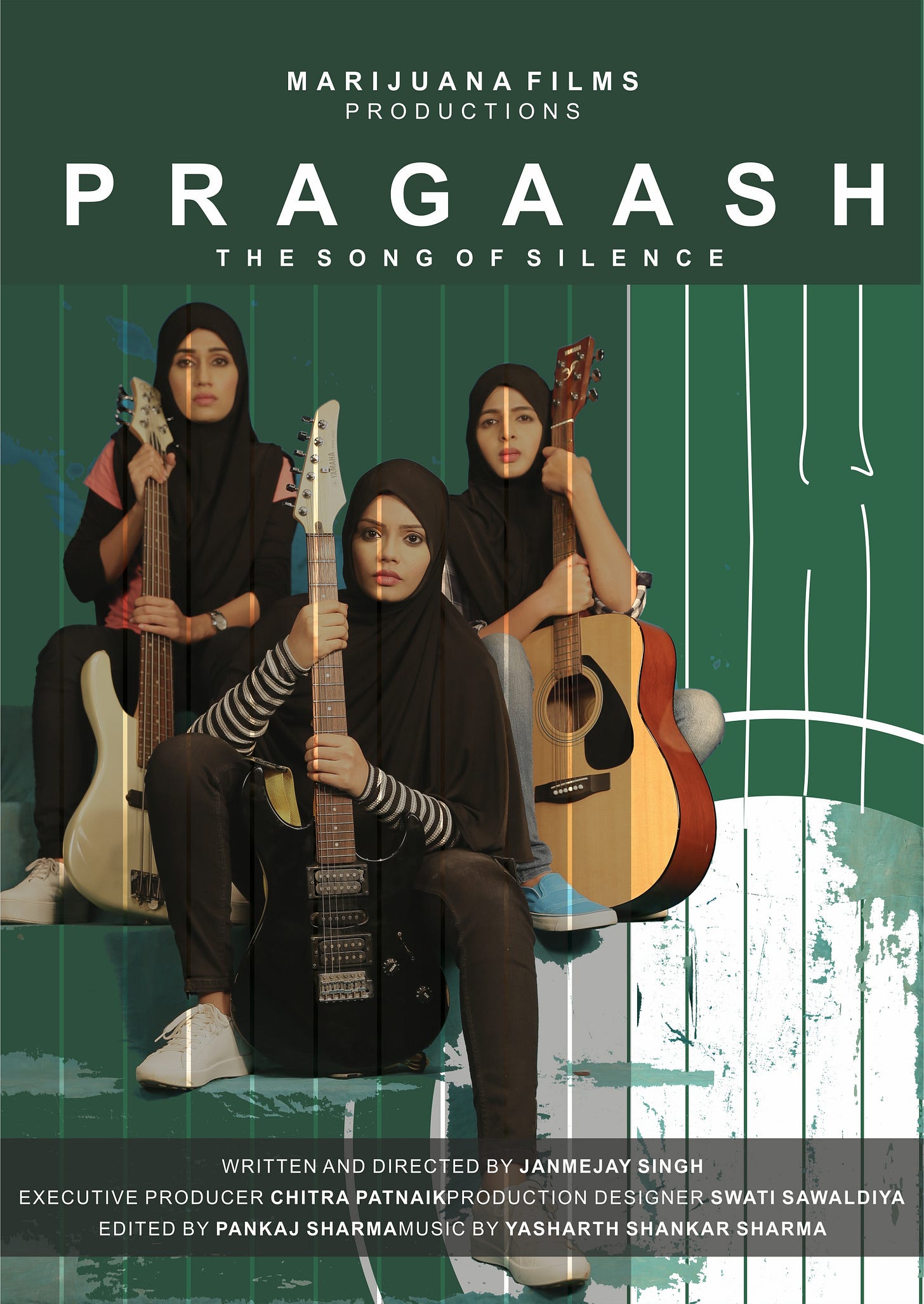

Here’s Kashmir, through the eyes of Ali Safuddin and Ruman Hamdani, the representation of a resurgent Kashmiri folk music scene:

I couldn’t go to Gurez due to the heavy untimely snowfall, but a kind local did send across some photos from Bagtore:

Ecological collapse

I’ve hinted, at various points above, that not all is well in Kashmir.

Terrorism. Untold military presence. Internet shutdowns. Gunning down of journalists. Censorship. Insurgency and separatism. Encounters. Exodus. Shutdowns of civic and religious spaces. Massacres.

These things happen in warzones, not thriving—or even functional democracies.

Laying out this context and atmosphere extensively was necessary, because it is within it, that a complete and total ecological collapse is taking place.

If you have survived clinical depression, or witnessed it at close quarters—you would know that depression makes it futile to even consider keeping ones space clean, let alone acting towards it.

The valley is down with a silent sickness.

“Action plans”, “reports” or “webinars” can’t cure this depression. They don’t even recognize it as such.

It’s like telling a depressed person to spend more time outdoors because surely, that will feel better.

There’s waste strewn all around, the rivers have started dying. Whatever is left is being plundered and taken outside the valley by thousands of heavy duty trucks every night.

This incessant outflow is propped up by a dystopian maze of flyovers, tunnels and rail corridors being constructed by the Indian state to connect it’s mainland with Kashmir—within a mountainscape that falls apart each time it rains.

In Srinagar, the street dogs have gone feral—always on edge, roaming around in packs, united by their disease ridden fur coats and complete excommunication from society.

There’s too much for even the hawks and mice to feast on.

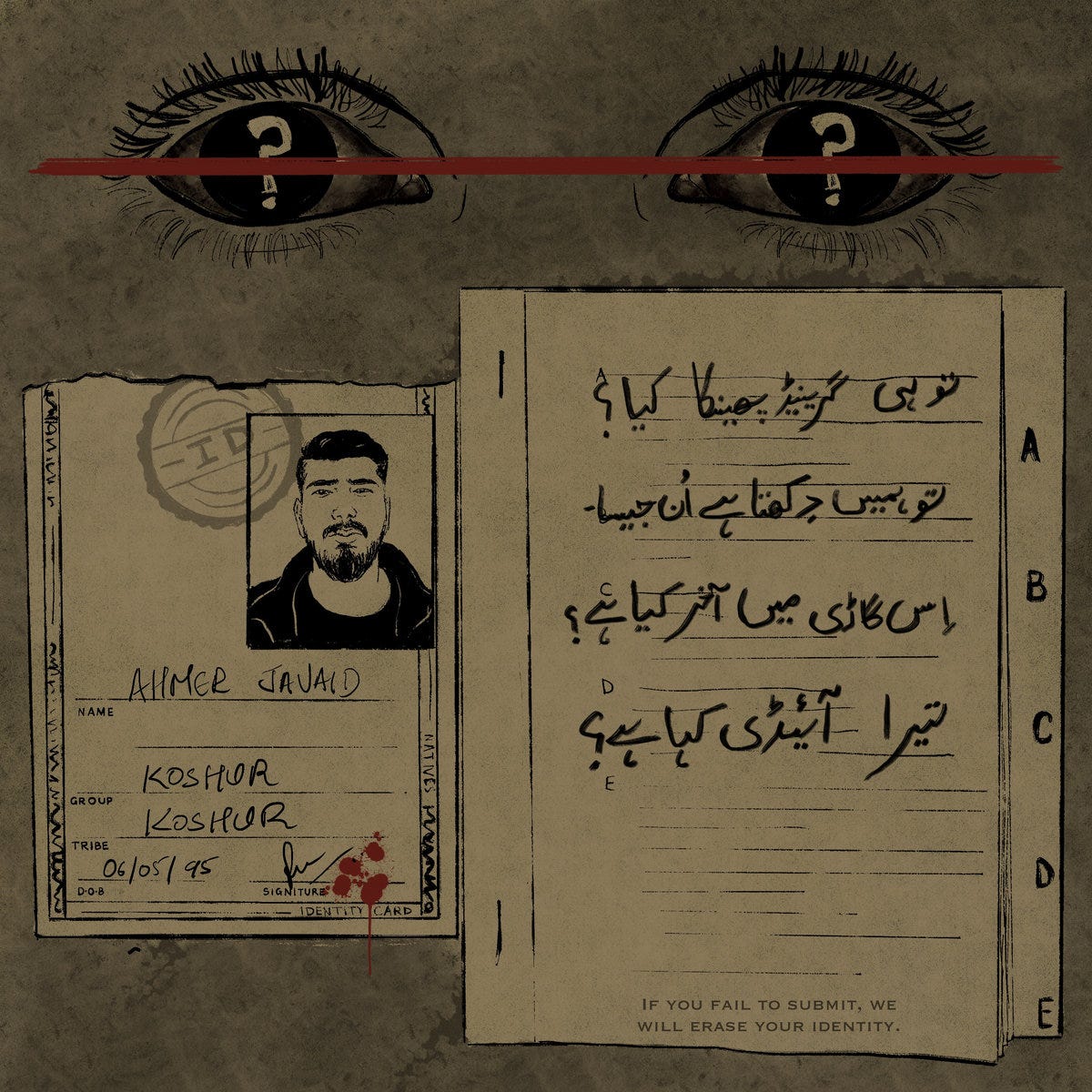

“The marginalization of ordinary Kashmiris only becomes more total, as India leapfrogs into a digital future”, someone said, hinting at the morbid metamorphosis of technology into surveillance and control—as it makes its way into the valley.

In light of the Pahalgam massacre—I cannot write more at the moment.

Do wait for the next part of this longread, for a structured and factual account of ecologically collapse in the valley—and the steps we have taken since the visit concluded.

Warmly,

Utkarsh Jain

Himalayan Advocacy Center

Postscript:

Hi there! Hope you enjoyed our second longform article for The Dhauladhar, where we delved deep into our experience doing environmental justice (EJ) work across Kashmir. Now that you’ve reached all the way, we recommend you pair this read with our documentary capturing the entire journey—that was funded by a generous community of our supporters.

Our aim with this longform format is to lay out the full extent of some of our advocacy work, as a nonprofit working on enhancing access to EJ in the third pole: a region extending through Central, South and South Eastern Asia—holding the largest freshwater reserves on the planet, outside of the two poles. We hope to coherently record our successes and failures in vivid and considered detail, for the benefit of present and future generations, and history.

With this longread, we wanted to demonstrate precisely what we can achieve in the tightest of budgets.

However, the truth is that funding is crucial for reaching and executing EJ work from borderlands such as Kashmir.

Funding our work helps us go all the way, and we’re willing to do just that!