[Hi there! Welcome to our first longform article for The Dhauladhar. In this format, we lay out the full extent of some of our advocacy work, as a nonprofit working on enhancing access to environmental justice in the third pole. Our hope is to coherently record our successes and failures in vivid and considered detail, for the benefit of future generations, and history.

If you’re new here, do check out our first issue about why we’re launching The Dhauladhar. If you have an Indian bank account, do consider supporting our work here. As always, enjoy viewing and reading!]

In April, 2024—a little over ten months ago, we initiated extensive right to environmental information work from our office in Dharamshala, India—inspired by Aruna Roy’s tireless efforts to hold the Indian state accountable to the people.

Since then, we’ve used the landmark Right to Information (RTI) Act to file hundreds of applications (including first and second appeals against denials to provide information, along with the follow up phone calls and emails) with the Indian state.

In this longform post, we take you through the ~2,300 pages of strategic environmental information we have obtained till now.

Our efforts continue to be entirely funded domestically.

Each time we filed an RTI application, we shared our story with the Government—emphasizing on our location and access to justice work, as well as the latest judicial orders in climate and EJ. In this way, we hoped to act equitably before seeking equity, and build on our legitimate claim to an environmentally just third pole, should the need arise in the future.

Here’s a meaningful quote we came across in the context of equity and its relationship with the law:

We continue to make all of this information open access, and accessible via a QR scan from our handbook across Asia, North America and Europe—including at the NUS, Bodleian, National Diet and the Lillian Goldman Law Libraries—supplementing our extensive outreach efforts within India.

As is with our ongoing documentation and mapping of the current state of Himalayan environmental law, the aim with this post is to permanently record our experience doing this work—for future and present generations alike, and for history.

The information we obtained describes in granular and unabridged detail as to how the Indian executive has considered and responded to planetary change, and the inner workings of the bureaucracy which maintains a record of these responses.

Information we obtained from the Union Government

At the Union level, our focus has been on broader issues implicating India’s obligations in the International legal system, and climate policy on the national level. Some of the institutions we approached included the President’s Secretariat, Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of External Affairs, and the Cabinet Secretariat—the top rung of the Indian executive.

We asked:

“When and how often did high level bureaucratic committees looking into India’s climate and natural disaster policy meet, and what did they discuss?”

“How did the Indian state respond to major developments in International Climate Law, including those coming from the International Court of Justice and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Seas?”

“To what extent has the Indian state considered international best practices when it comes to access to environmental information and justice—in this case, the Aarhus Convention and Escazú Agreement?”

“What were the inner workings behind developing India’s climate policy for the Kashmir region?”

“How and what has India been communicating with respect to its climate policies with the United Nations Special Rapporteurs, and how consultative has it been, prior to taking the stand that it took?”

As you might have inferred, we tried to unearth linkages that the record available domestically, might have with the international legal system broadly.

Why? To find out and archive the extent to which the Government elected by us has understood and applied the mandates (and indeed, the example) of international law—particularly with respect to transparency).

We believe that linkages established using RTI, in the form of the Government record, are a crucial initial step in enhancing accountability to the rule of law domestically—that like minded advocacy efforts of future generations can double down on.

We received multiple denials too.

The Ministry of Environment, for example, refused to provide us the record it held with respect to International Court of Justice climate proceedings, citing “strategic and scientific interest of the nation”.

Our appeal against the Ministry order is presently pending with the Central Information Commission (CIC) at Delhi.

We have also observed that sending in “notices of intention to file second appeals before the CIC” have also worked in obtaining information whilst avoiding being adversarial.

A bulk of information that we gathered came from committees, each helmed by high ranking bureaucrats with policy making powers: Apex Committee on implementation of Paris Agreement (AIPA), National Crisis Management Committee (NCMC) and the Prime Minister Council on Climate Change (PMCCC).

The direct influence of the Prime Minister in each of these committees was palpable, indicating a bias towards top-down, command and control policy making.

Some of our applications admittedly turned out to be misses, albeit potentially instructive for future action.

For instance, we failed to gather much information regarding the extent of the Ministry of Environment’s monitoring of climate change in Gilgit-Baltistan—a territory India claims as its own—despite Pakistan’s influence on the region, among other things, via its climate change authority.

Our attempt to obtain information on the status of Indian lithium mining operations in Catamarca, in the Argentine Andes met with little success too. The logic here was to learn about how India looks at lithium exploration within mountain ecosystems in other parts of the planet, keeping in mind lithium deposits identified in the western Himalayas.

Information we obtained from the State Governments

If there’s one word to describe our state level RTI work, it would be granular.

We managed to obtain a far more detailed account of the extent to which States had acknowledged and responded to climate change exacerbated natural disasters, particularly floods and landslides.

We use the word “exacerbated” with some responsibility here:

We did, however, face procedural delays—often running into months.

Bureaucrats were yet to fully embrace the RTI portals—which often required online transfers of our requests to relevant authorities, scanning, compressing and uploading PDFs, and accepting online payments.

We can’t overstate how new these workflows are to most bureaucrats outside of metropolitan cities.

Early into the process, we decided to target these barriers head on, seeking information on “Standard Operating Procedures” for online disposal of RTI applications—and using our findings as attachments with future requests, to impress upon bureaucrats that efficient disposal of RTIs is a mandate from the highest levels of Government, and the Supreme Court.

Here is what the States of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh made available in this regard:

We’re seeking similar SOPs from the newly minted RTI portal for the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir, as well as other Himalayan states.

On to our substantive findings—where we’ve made the most headway for the States of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh.

Himachal Pradesh

Our focus for Himachal was on the the fallout of haphazard planning across the state—primarily seen in the annual floods that grip (and devastate) the state each monsoon. We were particularly interested in those portions of the record where the State begins to reconsider (to say the least, or facts that would warrant reconsideration) existing developmental pathways, in light of the unique position of the Himalayan region in the times of climate change.

We have also obtained disclosures regarding planning related policy making too—where we obtained affidavits, proceedings and inter-departmental correspondences leading up to policies such as the Himachal Pradesh Draft Hill Conservation, Preservation, Cutting and Modification Policy, 2023, and the Himachal Pradesh State Action Plan on Climate Change.

Here is an example of recent correspondence between the State level Department of Science and Technology, and the Union level Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change—regarding filling key gaps in implementation of State Action Plans on Climate Change:

Uttarakhand

Our experience seeking information from the Uttarakhand Public Works Department was notably smooth. Probably the entirety of bureaucratic proceedings within the state take place in pure Hindi—even more so than Himachal Pradesh.

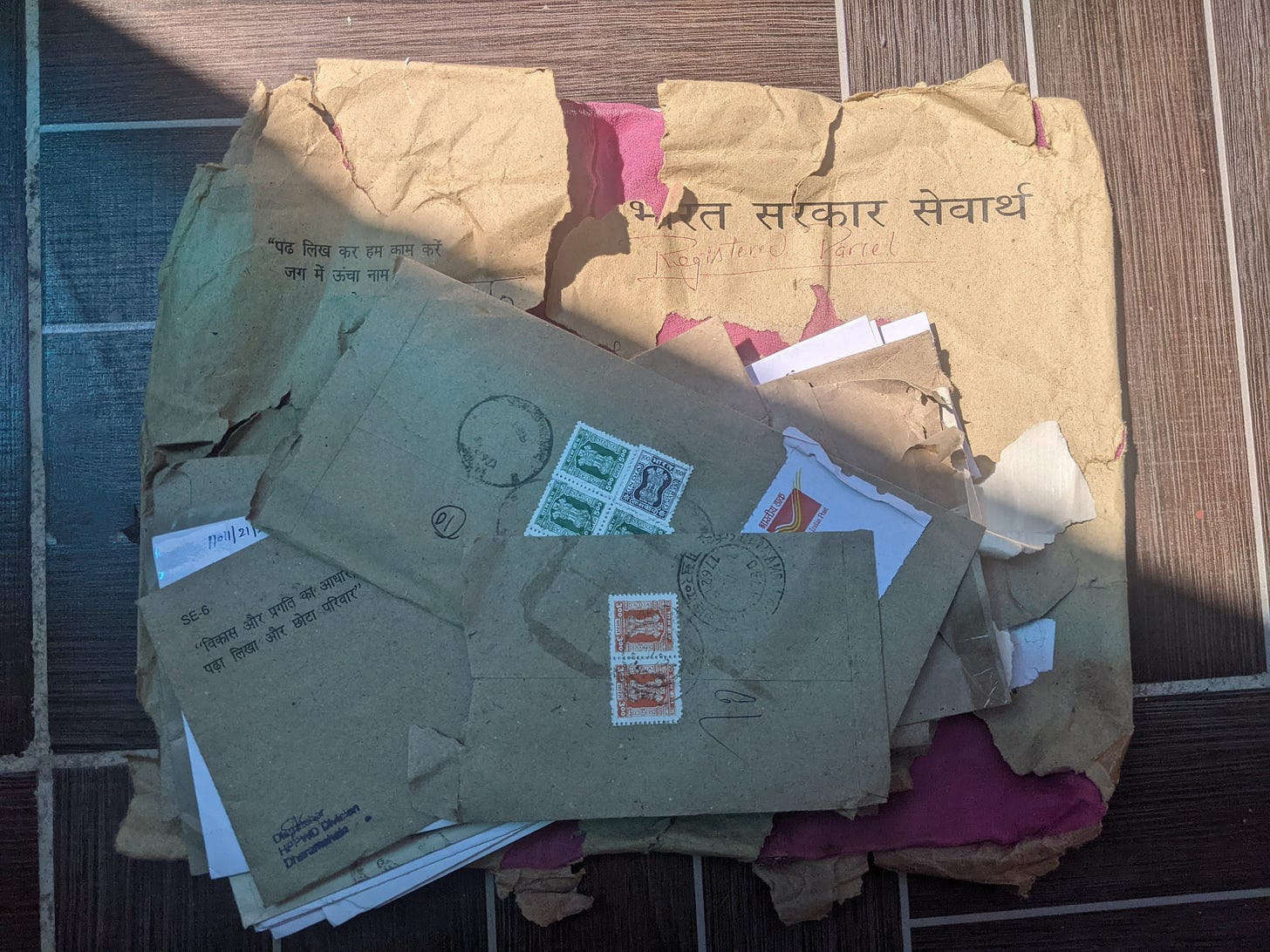

When we sought information regarding impacts of monsoons on road infrastructure maintained by the Department—the concerned officials reached out, seeking clarifications and sent in a whole dossier or information in print to us, free of cost. Here is what we learnt:

Further investigations at the State level

As you might have noticed, we’ve focussed on rivers/water, and related disasters like floods and landslides. There are many reasons to this, in addition to our obvious bias (Dharamshala witnesses some of the most intense monsoons in India, as well as crippling water shortages):

the sacred status of rivers and indeed their rights as potential legal entities,

the untold devastation that rivers in spate lead to each monsoon (when in fact, they are simply following their ancestral paths, destroying everything that comes in the way), and

looking at river basin dynamics as indicators of climate and planetary change

We’re doubling down on this focus—keeping what we see with our own eyes each monsoon front and center. Do reach out with your suggestions on how we can diversify from rivers, in a way that moves the ball forward!

Recently, we asked the Arunachal Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir and Uttarakhand Governments regarding progress on basin wide studies for the Siang, Chenab, Jhelum and Alaknanda—four rivers under immense anthropogenic pressure.

We’re also interested in other forms that water takes in the Himalayas— including glaciers, glacial lakes, snow, ice and reservoirs, and the anthropogenic threats to these.

Information we obtained at the Dharamshala level

Being located in Dharamshala, we have witnessed immense international interest in the Tibetan exile movement—centered around His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, and the Tibetan Government in Exile.

In fact, we once chanced upon an expert opinion from the late 1980s, prepared by Lester Nurick and William Lake of Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering (now Wilmer Hale)—on the legal status of Tibet as a nation state, at the Tibet Museum. Visits by delegations of Members of Parliament from across the world are commonplace here, and so is anti Xi Jinping sentiment (for obvious reasons).

All of this is to say that Dharamshala is an inspirational place to do the work that we do. It is, in many ways, one of the capitals of the greater third pole—attracting people from across the planet.

In reality however, tourists and locals alike have managed to plunder Dharamshala’s environment almost to a point beyond recognition. Tree felling and poisoning, ugly, unprofessional and dangerous architecture, solid waste and sewage mismanagement, unregulated sand mining—you name it.

To do RTI work locally, and therefore hold bureaucrats that sit in the same town accountable to the law is a different, and often far riskier ball game. We’ve marched on, though.

The delays with timely disposal of RTI applications, and sheer red tape were most prominent at the local level—with bureaucrats being largely unaware of the existence of an online RTI portal—or actively choosing to ignore requests anyway.

Earlier last year, we sought information from the District Magistrate, regarding sinking roads developing cracks (in particular, an arterial road connecting the main city to HH the Dalai Lama’s residence) due to sheer vehicular movement and unstable slopes—making them a threat to life.

Since then, the office of the District Magistrate failed to provide us with any information—instead resorting to the usual inter departmental transfers, hoping other offices to shoulder the “burden”. Ultimately, we were constrained to approach the Himachal Pradesh Information Commission. which will soon consider our second appeal:

[Update as of March 1st, 2025: We received a favorable order from the Commission, available here.]

Our focus for Dharamshala till now, has been on roads and tourism related issues—simply because these issues are front and center in how we experience the hill station on a daily basis.

That this town suffers from overtourism would be an understatement—and with it, come allied issues like too many taxis, broken roads and generally, a complete breach of ecosystem limits.

Water shortages that last months at end, are a direct result of over consumption by the tourism industry—that has a strong lobby with the local Government.

Over tourism during harsh weather also leads to casualties that often turn out to be fatal. We tried to investigate the legal authority and reasoning that informed administration decisions restricting tourist activities, like trekking and paragliding during winters:

The tourism industry in Dharamshala has long violated planning laws under the garb of the spiritual atmosphere—and we believe that has got to stop. Even those that are well intentioned with their entrepreneurial ventures have ignored the law.

Going forward, our aim will be to collect more information on the tourism industrial complex—and put it in the hands of the public. Using these documents to write to authorities, seeking action is also potentially on the cards.

After all, how can we destroy a town as beautiful as this:

Final thoughts

This was single handedly the longest, most detailed and technical newsletters we have put out till now at the Center—and it has been months in the making.

In India, we often see Right to Environmental Information work exist in siloes—with everyone in their own rabbit holes.

We wanted to change that, and make the entire process and learnings, imperfect as they might be, open access—both online and offline (all our work is accessible from various parts of the world, at the scan of a QR).

Anyone navigating the majestic Himalayas has the right to know what the state of its environment is, and what public authorities are doing to address these complex issues. Environmental information such as what you just witnessed—must ideally cross borders and inform how we look at the third pole as a whole region.

We will keep working towards these goals, and of course, keep you informed in the process.

Till next time, where we will hopefully tell you about our field visit within the Kashmir valley!

Himalayan Advocacy Center

Postscript:

As you may know, we are a small non profit in the environment + law space located in the Indian Himalayas. We are completely bootstrapped! This means no foreign funding and no fancy headquarters - just a small community—of which you all are an integral part—in the long run we hope!

What’s more - we, at the Center, are determined to localise efforts for the planet, without compromising on the best that the law has to offer. If you have the means, and want to support a committed local undertaking, please do consider contributing to our corpus. We hope to pleasantly surprise you with detailed information on where you money has been spent.